Clairac, French cradle of the Dutilh family

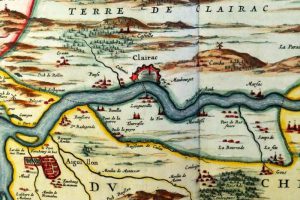

For fifty years, between 1570 and 1620, the small town Clairac was at the heart of the profound changes regarding religion, economy and politics of France in those days. How come that an agglomeration with an estimated population of about 3000 to 4000 inhabitants could have had such an importance? Let us try to find some answers.

Clairac, an abbey unlike any other

Active since the 11th century, the Benedictine abbey located in the heart of Clairac, overlooking the river Lot, quickly grew in importance, with up to 150 monks; at the time it served most of the land along the Lot and the hills surrounding it. Its abbots were often appointed from the local nobility. Though the legend lets it go back to Pépin-le-Bref (8th century), there is no proof of this age. The destruction of its archives during the Wars of Religion has removed all traces of its early ages.

Destroyed during the Hundred years’ war (1337-1453), during which it changed on several occasions between French and English domination, Clairac quickly resumed its importance, and even contributes in 1526 to the payment of the ransom of François 1st, who was captured by the Spaniards.

As an important landowner, the Clairac abbey very probably was the origin of two local products which had not only French, but also international success. In the gardens of the abbey the prune from the Near East was planted and grafted which gave birth to the famous plum and its “Agen prunes”, whose trade ensured the inhabitants of Clairac a substantial income.

Also on the lands of the abbey the cultivation of the “herbe à Nicot” (tabac), introduced in France by the monk André Thévet around 1550, has been developed. From the beginning of the 17th century, tobacco was one of the first sources of income for Clairac. Today, tobacco and plums are still grown on the banks of the Lot.

In the beginning of the 16th century, the ideas of the Reform, initiated in the South-West by Marguerite d’Angoulême (Marguerite of Navarre), sister of the king, started to circulate in France. In 1530 she decided to nominate Gérard Roussel as the abbot of Clairac. He never converted himself, as his idea was to reform the church from within, without forcing a split, and with that idea he favoured the diffusion the ideas of the Reformation, drawing with him the population of Clairac; for instance by bringing the consuls of the city under the governance of the abbey. In April 1534 Calvin visited Roussel, who he knew quite well, in Clairac.

Geoffroy de Caumont succeeded Roussel and he converted to the Reformation. Since then the monks followed his example, burned their ecclesiastical habits and started to get married. Since then Clairac would be one of the most active places of the French Reform, both by the actions of its pastors as by its energetic role in the diffusion of the new ideas.

In 1563 the vigorous maréchal de Monluc besieged and conquered the city; though he saved the inhabitants, he required a fine of 30,000 pounds. In 1568, Geoffroy de Caumont, who still received the benefits of the rich abbey, married Marguerite de Lustrac; it is said that he received an annuity of 100,000 pounds…

The following year, admiral de Coligny, at the head of the Protestant army, resumed Clairac. This gave a short period of rest, validated by the peace of Saint-Germain, signed in 1570, but which was broken in 1572 by the massacre of St Bartholomew. In 1574, Clairac was again besieged by the Royal forces. As a result of these repeated assaults, the bulk of the abbey and its monastic buildings was demolished.

Clairac, city without a Lord

The power of the abbey of Clairac had another consequence: while the abbot held power over both civil and criminal jurisdiction of Clairac, it never saw a great noble family at its head. If the village retains even today several strong houses, and rich mansions, it is only goods belonging to the bourgeois, or nobles of rather low origin. Keep in mind this peculiarity, which partly explains the richness of the Protestant bourgeoisie of these last years of the 16th century.

The power of the abbey of Clairac had another consequence: while the abbot held power over both civil and criminal jurisdiction of Clairac, it never saw a great noble family at its head. If the village retains even today several strong houses, and rich mansions, it is only goods belonging to the bourgeois, or nobles of rather low origin. Keep in mind this peculiarity, which partly explains the richness of the Protestant bourgeoisie of these last years of the 16th century.

1576 : the alienation of church property, or how the land fell to the Reformed

In the second half of the 16th century the state impoverished, particularly because of French internal conflicts. Also, thanks to an exemption granted by Rome, cardinal of Lorraine implemented since 1572 a policy of systematic sale of church property, to replenish funds of the central Government; among these properties, there were many belonging to the abbey de Clairac, which surrendered in 1576. And who were the buyers? Clairac bourgeois families, Protestant faith, who were hitting two birds with one stone: they increased their incomes at the expense of that of the abbey.

It is reasonable to believe that the social rise of certain Dutilh’s was one of the examples of that: in fact, in the middle of the seventeenth century, when the family counted in principal only craftsmen (shoemakers, tailors, carpenters etc), some of them acquired a new status while obtaining a certain fortune in trade, like Moïse Dutilh and his son Abel who, following his marriage with Marie Breton, made numerous land purchases.

Probably the combination of successful business operations arising from exchanges with the first members of the family emigrated to Holland, and new charges of tax farmers-general, among which the Dutilh’s, were able to manage the assets of these large protestant bourgeois families, enriched with their recent acquisitions.

1604 : a converted king who offers the abbey

In 1589 king Henry of Navarre became king of France, under the name of Henry IV. Four years later, he converted to the astonishment of the Reformed of his native South-West. In 1598, he proclaimed the Edict of Nantes, intended to mark the end of a religious war which had put France to fire and in blood for over half a century. Six years later, to finally get Rome at his side, “good King Henri” gives Clairac abbey to the chapter of Saint John Lateran, in Rome.

Since then, while the abbey of Clairac is no longer a modest establishment, its huge revenue – it must be remembered that the plains of Lot and Garonne are among the richest lands of France – are managed by a mostly Italian abbot, directly appointed in Rome, whose function is rather that of an administrator than that of an abbot. Lord of the city, he appointed consuls and municipal officers, and enjoyed the rights of high, middle and low justice. And so we see a Catholic abbot appoint as the municipal authority in a Protestant majority! The parish church of Clairac – Saint-Martin – having been razed by Protestants, is the church of the abbey which became parish. Protestants have a temple probably built on the remains of Saint-Martin…

1621: different king, different siege

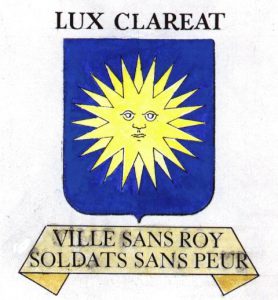

The moment has come to remind of the motto of Clairac: « Ville sans roi, soldats sans peur » (town without king, soldiers without fear)2. The very peculiar status of Clairac, the richness of its abbey whose income went to Rome, the growing prosperity of a Protestant bourgeoisie, owner of the land particularly thanks to the sales by the cardinal of Lorraine, all this helped strengthen the rebellious side of Clairac, wishing more and more to detach itself from its stranglehold..

The moment has come to remind of the motto of Clairac: « Ville sans roi, soldats sans peur » (town without king, soldiers without fear)2. The very peculiar status of Clairac, the richness of its abbey whose income went to Rome, the growing prosperity of a Protestant bourgeoisie, owner of the land particularly thanks to the sales by the cardinal of Lorraine, all this helped strengthen the rebellious side of Clairac, wishing more and more to detach itself from its stranglehold..

The walls have been rebuilt after the onslaught of 1574, and the Protestant Assembly of La Rochelle in May 1621 called all Protestants to weapon. Both and so the young King Louis XIII decided to restore order in this remote province, and came himself, on 20 July 1621, to lead the Clairac headquarters. Only after two weeks his armed forces overcame the wild resistance of the Clairac inhabitants: only four of them were sentenced to death by hanging, a 150,000 pound fine was imposed (and partially offset soon after by the King); the ramparts were once again dismantled.

1621-1685 : more than sixty years of difficult collaboration

Since the end of the 16th century, the inhabitants of Clairac went away in exile, to live their lives in more favourable countries like Switzerland, The Netherlands and Germany. The family-ties, so tight in those days – and still in the Dutilh-family – led to a trade primarily with brothers, cousins, friends who stayed on the banks of the Lot; They set up an international trade which grew regularly, and generated the prosperity of families like the Dutilh family. Because throughout the reign of Louis XIV, bullying and persecution seriously increased, until the fatal Revocation of the edict of Nantes in 1685, which widely opened the doors of emigration: only one choice was left to the children of the reformation: conversion or exile.

Since the end of the 16th century, the inhabitants of Clairac went away in exile, to live their lives in more favourable countries like Switzerland, The Netherlands and Germany. The family-ties, so tight in those days – and still in the Dutilh-family – led to a trade primarily with brothers, cousins, friends who stayed on the banks of the Lot; They set up an international trade which grew regularly, and generated the prosperity of families like the Dutilh family. Because throughout the reign of Louis XIV, bullying and persecution seriously increased, until the fatal Revocation of the edict of Nantes in 1685, which widely opened the doors of emigration: only one choice was left to the children of the reformation: conversion or exile.

At the same time the 17th century saw the decline of the abbey, deserted by its monks, forgotten by its abbot. No major architectural programme could restore the dignity and beauty of previous buildings. The abbey of Clairac – apart from its revenue – was no more than a shadow of itself. In the 18th century it was falling asleep, having just more than meagre belongings to exploit.

The confessional strength in the area around Clairac in 1660 is shown in the figure3.

Lights on Clairac

It is particularly in that period that a new actor enters the scene: Montesquieu. Following his marriage to a rich girl from Clairac, Jeanne de Lartigue, the philosopher from Bordeaux was closely monitoring the income from the property of his wife in particular the considerable vineyards. In those years several enlightened minds from Clairac grouped around Montesquieu in the scientific society at Castle Clairac. That society included Jacques de Romas and the brothers Louis and Mathieu Dutilh de la Tuque. De Romas was an enlightenment scholar who, in 1753, carried out an experiment using a kite in a storm proving that lightning is a form of electricity. This was similar to Franklin’s famous experiment but carried out in ignorance of his work and in the presence of witnesses. The Dutilh-brothers were instrumental in that work, as they have built the kite with which De Romas carried out his experiment on their estate.

It is particularly in that period that a new actor enters the scene: Montesquieu. Following his marriage to a rich girl from Clairac, Jeanne de Lartigue, the philosopher from Bordeaux was closely monitoring the income from the property of his wife in particular the considerable vineyards. In those years several enlightened minds from Clairac grouped around Montesquieu in the scientific society at Castle Clairac. That society included Jacques de Romas and the brothers Louis and Mathieu Dutilh de la Tuque. De Romas was an enlightenment scholar who, in 1753, carried out an experiment using a kite in a storm proving that lightning is a form of electricity. This was similar to Franklin’s famous experiment but carried out in ignorance of his work and in the presence of witnesses. The Dutilh-brothers were instrumental in that work, as they have built the kite with which De Romas carried out his experiment on their estate.

But the inhabitants of Clairac did no longer support the administrative power of its Italian abbots, who retained the rights of low and high justice. In 1792, they found the abbey deserted by its abbot. In 1799 it was sold as National Property for warehouse, to the receiver in Clairac, soon afterwards ceded to Changeur, banker in Bordeaux, and finally bought by de Saffin, at the time mayor of Clairac, whose heirs were owners until the mid 20th century.

[For further information, there are for instance numerous articles (in French) in La Revue de l’Agenais, as well as in Jean Caubet Histoire de Clairac]